THIS IS FLESH

On Toni Morrison, Writing at 55, and Learning to Love the Body That Carries You

Dear Reader,

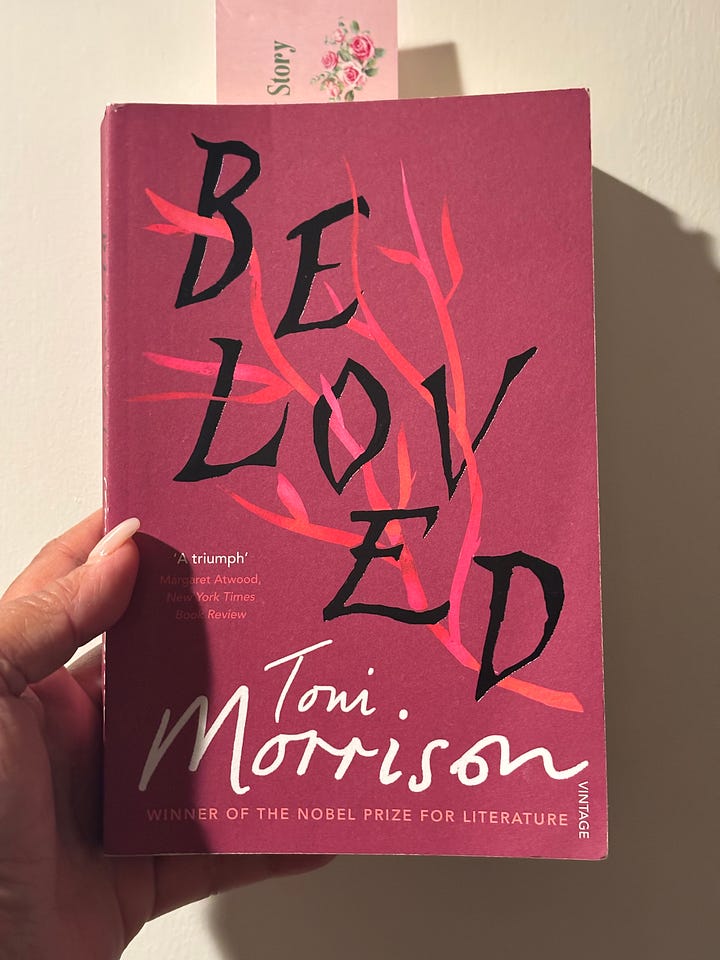

There’s a passage I return to often, like a psalm or a piece of jazz I can’t stop humming. It’s from Beloved, Toni Morrison’s towering elegy for memory, mothering, and freedom:

“This is flesh I'm talking about here,” Baby Suggs says. “Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms I'm telling you… Love your heart. For this is the prize.”

Lately, I’ve been thinking about what that means- for women of color like me, for mothers, and for anyone who has spent years surviving when they longed to live. I’m fifty-five now. Newly single. Both daughters grown. Writing at last. And what I’m learning, slowly and surely, is how to love the heart that carried me through.

Below is an essay that began in my journal, took shape without much ceremony, and now feels like a declaration. It’s about the body. The beginning again. The breath you didn’t know you were holding. It’s about listening to the voice inside you that sounds a little like Morrison, a little like your grandmother, and a little like the version of yourself you almost forgot.

Thank you for reading. I’m glad you’re here.

-Carmen Evelyn

06.12.25 Los Angeles, CA

There are mornings now when the mirror no longer startles me. The face staring back is both familiar and newly ungoverned, as if it finally got permission to step out of the waiting room it’s lived in for decades.

There is a quiet astonishment in being fifty-five and realizing that, for the first time, you are becoming known to yourself. The face in the mirror no longer startles- it stares back with a kind of weathered dignity, unhurried, unwilling to be softened or disguised. You greet it not with correction, but with recognition.

The changes in your body- the new aches, the altered contours- begin to feel less like failures and more like revelations. This, you think, is what it means to arrive.

After 25 years of marriage. After motherhood. After the structures that framed and at times, confined a life, begin to dissolve, you are left with something resembling freedom. And it is in that clearing- psychic, emotional, literal- that the words of Toni Morrison return with startling clarity.

The page has become a refuge, a chapel. Each sentence an altar. Each word a hand resting on the shoulder I used to give to everyone but myself.

And it is Baby Suggs who meets me here, the spiritual center of the novel, stands before a gathering of once-enslaved people and says, “This is flesh I’m talking about here. Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms I'm telling you… Love your heart. For this is the prize.”

The passage is often cited for its lyrical power, but I find myself returning to it now not for its poetry but for its precision. Morrison knew that liberation is not abstract. It is not only political or theoretical. It is somatic. It resides in the body- in our ability to reclaim the very flesh that has borne witness to all that we have endured.

When Morrison wrote those lines, she carved scripture into the spine of womanhood, and gave permission to tend to the flesh after all the proving and serving and surviving were done. She named the body not as burden, but as altar.

And now, at this age, I understand what that altar demands: Attention. Reverence. Rest. Not as indulgence but as a practice of resistance. To love the heart is to live in refusal of every voice- external or internal- that said you must earn your worth through depletion.

And for me, liberation has meant beginning again. I am divorced. Both daughters are grown. I am writing now, not as a declaration but as a necessity. It is the practice I return to daily, without ceremony. A form of breathing. A quiet rebellion against all the silences I once maintained for the sake of others.

This new life is not about reinvention, which often implies a disavowal of the past. It is about continuation. A refusal to truncate the self in favor of palatability. It is about taking what has been lived and threading it into something legible, something whole. I am learning to write in a voice that has been tempered by decades of observation, compromise, tenderness, and loss. It is a voice that no longer seeks approval.

I walk differently now. Not faster or slower, but with intention. I feed myself with more than food. I say no with my full chest. I take naps without apology. There is no guilt here. I say “I don’t know” like a poem, because curiosity is more sacred than certainty. I kiss myself goodnight in the dark. I read Morrison aloud when I feel forgotten, as if her words are a balm written just for me.

And I write. Every day. With the urgency of someone who knows what it feels like to be voiceless and polite about it. I write to remember. I write what I don’t know about. I write to unearth what I buried under marriage, under motherhood, under the weight of being someone else’s sanctuary.

To write at this age is to write with the knowledge that time is not infinite. It is to accept the body as both archive and instrument. The hands that type these words are the same hands that once rocked babies to sleep, that cooked too many meals, that gripped the edge of the sink in despair. They are no longer apologizing for what they cannot do. They are committed to what they can.

And what do we do with this new life, this freedom born of fracture?

We score it. We improvise. We let it moan and soar. We speak to the spirit in the key of self-forgiveness. There is no template. No manual for beginning again at the moment everyone else thinks you’ve reached your end.

The culture doesn’t know what to do with a woman like me: ‘unpartnered,’ unbothered, unbossed, and blooming. I’ve learned to be an alchemist, coming out of the fire humming, licking the soot, and dancing on the ashes of the bridges that I chose to burn.

I live now by rhythm, not rules. I wake with the sun not out of duty but devotion. I stretch with gratitude for the body that carried me through. I dress in colors that remind me I am alive. I delete messages that feel like shackles. I call my daughters and remind them that they do not belong to anyone but themselves. I do not answer questions that start with “Why didn’t you…”

I listen to Lee Morgan when the silence is too sharp. I light candles when the ache rises up from memory like smoke. I cry when I need to. I laugh when I don’t expect to. I eat oranges slowly. I make room in the bed like someone expecting a miracle. And always, in the background, Baby Suggs is preaching: This is flesh I’m talking about here.

Yes, it is.

This is the flesh that broke and mended.

This is the back that bent over cribs, bent over stoves, bent over grief.

These are the feet that walked away.

These are the arms that held the world until they shook.

This is the heart that no longer asks for permission to be loved.

When Morrison writes, “Love your heart,” she is not offering a metaphor. She is instructing us to locate ourselves in the very center of our longing. To love the heart is to acknowledge all it has withstood. It is to stop negotiating with exhaustion, to stop mortgaging joy. It is to rest. To write. To walk differently through the world- not faster or louder, but with more precision, more care.

There is no script for this kind of life. The culture often struggles to imagine women beyond a certain age unless they are exceptionalized or diminished. But what I want is neither martyrdom nor magnificence. I want room. I want the soft hum of a day well spent. I want sentences that stretch. I want mornings that begin with coffee and not crisis. I want to be remembered not for what I endured, but for what I made.

I think of Baby Suggs in the clearing, not as a relic of fiction but as a model of something real: a woman, born into brutality, insisting on joy. Standing in her body and saying: Love it. Not because it is perfect, but because it is yours. Because it is here.

I think of the clearing now not as a place in the woods, but a metaphor for this life after life. A wide open space where I can shout my own name and hear it echoed back not in someone else’s voice, but in my own.

At fifty-five, I have learned to listen for that voice.

I light candles not to summon peace, but to acknowledge it when it comes. I read poetry aloud, not to be moved but to be mirrored. I write, and then I rewrite, and then I leave things unfinished because I can. I walk barefoot. The flower now sits behind my right ear, not the left. And I cry without preamble. I no longer explain.

And, always, I return to Morrison- not as theory, not as study- but as invocation. This is flesh. This is the prize.

Thanks for doing this. Provides a much needed contrast for someone on the other side of things– starting out in life.

Appreciate the realness you bring, I love Toni Morrison.